Previously:

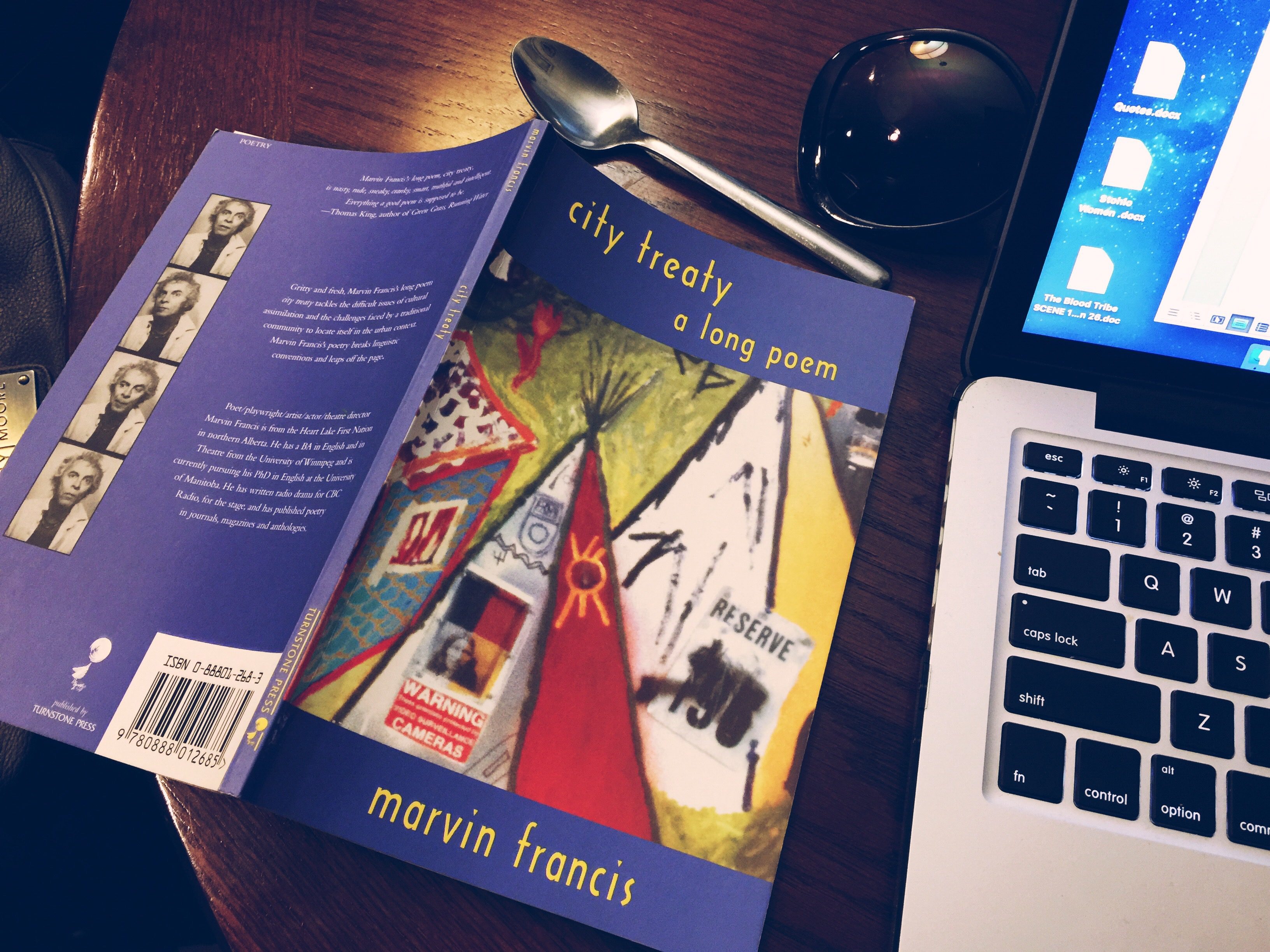

City Treaty: A Long Poem had several interesting statements or lines that I felt were relevant to the current discussion of what Urban Indian is, although it was hard to follow the first time I read through. I found that I had to “let go” of my ideas of what should be in a poem, and allow myself to experience the poem as it was. And it was a long story, with several different stories spanned into one long form, much like an oral narrative, which was appealing. I read out loud, and that made it easier to connect with, to hear the rhythms and natural oral voice emerge.

With lines such as “there are 25 street smiles you better learn when you / sell your body” (25) and “the electric indian rides tall / john ford john doe run johnny run” (39), this collection breaks down stereotypical native imagery and talks about the struggles that Indigenous women face – especially relevant as we just finished talking about MISSING SARAH: A MEMOIR OF LOSS, a non-fiction work written by the sister of a women whose DNA was found on the Pickton farm. This book rejects traditional forms of poetry books – there are no neatly ordered poems per page, and barely any indicators that you have moved on from one poem to another aside from a bold title here and there. Francis takes on Treaties to Government to Shakespeare to the indulgence of Fast Food to stereotypes – nothing is safe, nothing is sacred, and perhaps that in itself is a statement – as nothing in our cultures seems to be sacred or off-limits to the general population. There is very little said on the topic of land, and how that plays into urban identity, if at all, in this book. Is the lack of land in itself a statement as well – that land is forever changing and that he and his writings do not exist in government-given borders, or that land is a structure that does not define culture? That his identity is not focused on land, but rather story, language and community? I do not know the answer, but it it something to think about. (November 2014)

Currently:

Having reread this, I still really enjoyed it. There is a long poem written in the top corners of the pages that took me a while to figure out, and I appreciate that. I like the idea of a hidden narrative being placed in plain site, and a continuation of a discussion throughout as we read and immerse ourselves in the already tightly-written and layered main poems and stories. I think this book is a hidden gem, and speaks directly to the conflicts that a lot of both Urban and Reserve FN’s experience today.

Visual Indian – p. 39

This is a poem speaking about the visual stereotypes that started/became popular with the emergence of Western Movies. The poem mentions that for the recipe of a western movie, all you need to do is “add some tonto / a bit of apache some ojicree some Navajo some aztec” referring to the blending of every bit of popular culture to create the idyllic Indian in movies. It’s not about being culturally specific so much as easily identifiable as other. And when you mix in “the noble / savage” and add a captive, it become a time for John Ford Western.

The poem’s second half, if it even can be considered so, shows a narrative of the wild west Indian to the Urban Indian, speaking of “when you live inner / city feathers plastic” as a “motorcycle mascot,” when your visual identity is now conceived to be the only acceptable way that society wants you – as a token of back when, as a people who are not “real” as we no longer live the way we used to, and since we “never chopped wood / virtually only” our existence then ceases to be valid.

Treaty Names – pg. 11

The transition from the naming by your community and your actions to the simplified, English re-naming/colonization is outlined in the line “running wolf wolf collar sam wolf” referring to how they tamed the running wolf, they collared him, and now he is Sam. That this renaming is mourned when “history howls at the new story line.”

That we need to walk through the stories in the land, to see the families behind the figures. We need to delve into the names and see when the “feather fantasy” – that image of the feathered Chief standing tall against the plains skyline – is just “crow turned feather” – it’s just mainstream renaming and picking one bit of our culture or identity and hanging onto it, moulding it and renaming it, to suit them.

Fuck Your Colonial Euro-Attitude Dudes – pg. 47

This is a straightforward, in your face poem about the use of Indigenous faces and characters in mascot use. It’s pretty blatant with “Fuck Mohawk gas / Atlanta braves / Cleveland indians / Washington redskins / THE KANSAS CITY CHIEFS.” It’s calling out the little things you don’t think about – just do – such as sing “One little / Two little / Three Little / Indians” and call it just a children’s song. It’s a concrete reminder that the current fight to end the usage of Indigenous names/images in mascots has been around for a long time, as the book was printed in 2002.

It’s a hard hitting poem, short bursts of hard language that speak directly of the “cigar store stoic” and that society, as a whole, should lose the idealism and stereotypical imagery that comes from “the noble and not so noble / Savage lost in the B movie” but that image is perpetuated with the constant reinforcement of the idealization of westerns, the tightly fisted gripping of what main stream media wants to portray Indigenous people as.