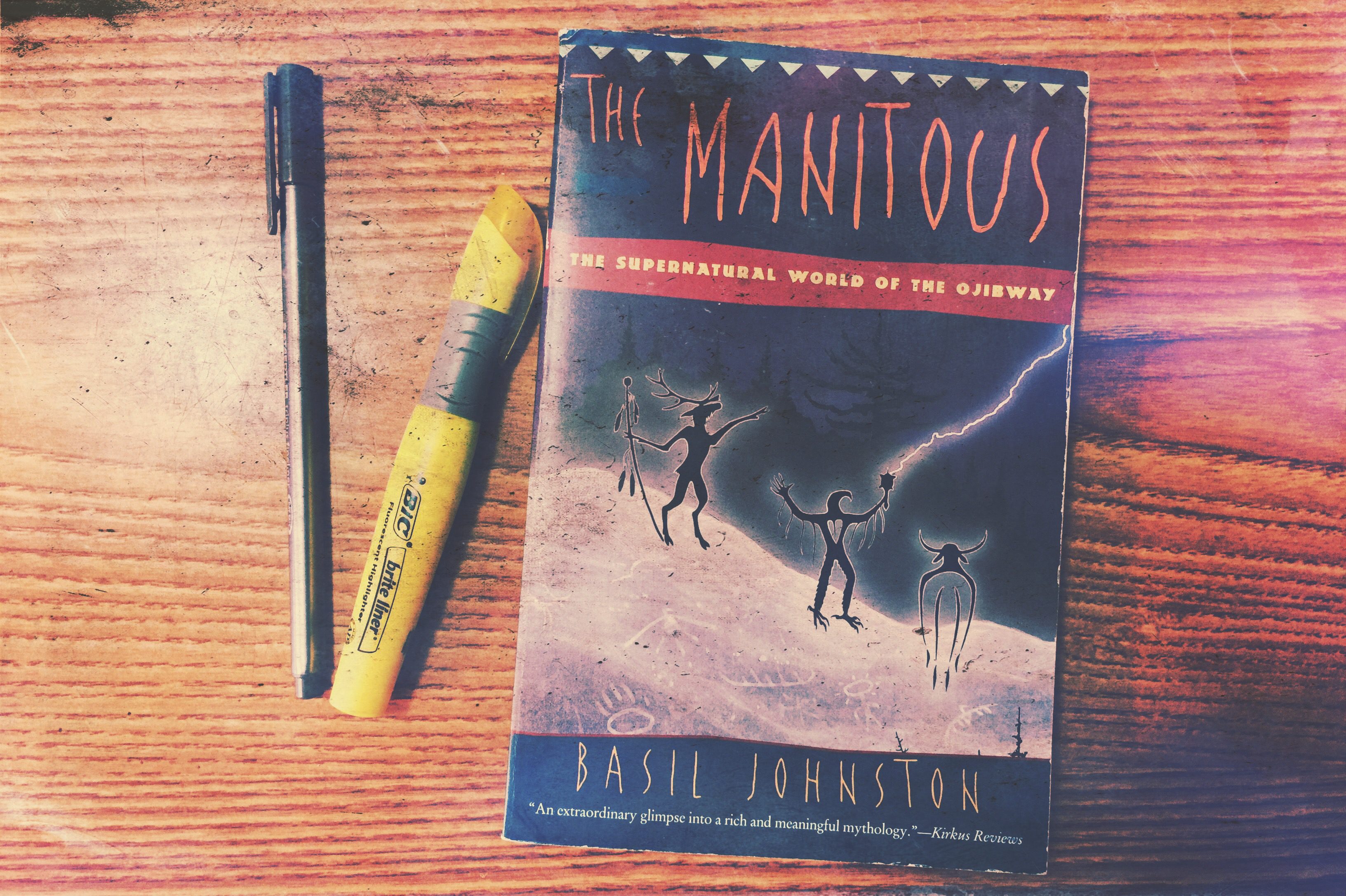

This book was published in 1995. I had some initial confusion as the dedication page refers to the Anishinaubae, the front cover says ‘Ojibway’ and the back cover says ‘Ojibway (Chippewa).’ I will refer to the Indigenous people within as Anishinaubae, although the author also wavers with stating Ojibway himself within the text.

This book is about the Manitous, spiritual beings within Anishinaubae culture. In his preface, Johnston shares that he has always had an interest in Manitous and that by the time he was a young adult, “my interest in the manitous was no longer casual; it had now become fascination. Stories about the manitous allow native people to understand their cultural and spiritual heritage and enable them to see the worth and relevance of their ideas, institutions, perceptions, and values” (xiii).

In the beginning, we are introduced to Kitchi-Manitou (the Great Mystery) and Geezhigo-Quae (Sky Woman). Litchi-Manitou is the Manitou who created the world, the birds and animals and lands and mountains and lakes, and then it flooded. But while it flooded, Geezhigo-Quae conceived in the skies. The Giant Turtle was one of the last remaining animals, and he allowed Sky Woman to sit on his back. The muskrat brought up soil, land was created, Sky Woman gave birth to twin sons. And so on (read the book, it’s actually pretty great) but the premise being that the Anishinaubae’s beings started on Turtle Island – their creation point starts here, not in a journey from other islands (xvi).

The Anishinaubae grew to be a people of “hunters; fishers; harvesters; homemakers; healers; storytellers; and, only as a last resort, warriors” (xvii). They worked hard, they worked to survive. They had joy and laughter, and they also felt the obligation “to the community that required them to give something back to the people for all the benefits and favors they received” (xix). The youth were taught by the elders, and it was during these lessons of the nightly, winterly teachings that they learned of the manitous – “their origin; presence; dwelling places; services and purposes; and kinship with all living beings, including plants, Mother Earth, animals, and human beings” (xx). The manitous were powerful beings, with only two that could be evil (Weendigoes and Matchi-auwishuk) and the manitous carried jurisdiction over multiple parts of life – the arts, the successful hunting trips, the ability to storyteller, the four directions, etc. These stories are the basic ones, Johnston says, so that people can learn an listen to them and begin the process of preserving their Anishinaubae culture (xxiii).

Chapter 6: Nana’b’oozoo (p.52)

Nana’b’oozoo able to talk from birth. His father was a manitou, his mother was a human. After his birth, his mother died and he was left to be raised by his grandmother. In the stories, he is the most human-like in appearance and attitude – often becoming embroiled in follies of his own making, due to his own impatience or ineptitude is listening to his elders or teachers, and rushing off to do it his own way. He was originally timid – everything scared him. But when he learned, years later, that he was not an orphan so much as a cast off, he decided to avenge his mother and kill his father, a manitou. Welllll, that didn’t go so well. Even though many people advised him against it, he had to try. When he and his father fought, Nana’b’oozoo was defeated and lay down, covering his eyes, waiting for the killing hit… only to open his eyes and have his dad tell him to sit up (all paraphrased badly, read the book – pg.69). He was gifted the peace pipe to bring back to his people, to represent reconciliation.

Nana’b’oozoo liked children and accidentally created butterflies which made them laugh an get rid of a sullen sickness (76). Nana’b’oozoo had compassion for all his friends, and sometimes got them hurt when he rushed out to help instead of listening to their problems first (81). Nana’b’oozoo was too curious for his own good and often wondered about female problems – what did it feel like to be a woman and desired, what did women do in secret during their moon-time, etc (81). Nana’b’oozoo loved his grandmother but felt that she often took too much of his time as he got older and she got older and slower, so he abandoned her one day but felt too guilty and came back (87). As he grew, he made less and less mistakes, but it so happened that the Anishinaubae called people who made foolish, prideful mistakes Nana’b’oozoo, shaming them into the correct actions. In the end though, Nana’b’oozoo left his family and his ancestral lands with his grandmother at his side. He has not been heard from since. With the loss of the language, his story is unlikely to return (95).

Chapter 13: Weendigo (p. 221)

The Weendigo is an evil manitou that is larger than humanly possible in height, be it a man or woman. It is always “on the verge if starvation” (221) and smells like “a strange and eerie odor of decay and decomposition, of death and corruption” (221). The more a Weendigo eats, the hungrier it gets. There is no satisfaction in its hunger.

There are two ways to become a Weendigo.

A man is made a Weendigo by a sorcerer. The man had asked the sorcerer for a talisman to help find food and allay his hunger (225). The man took a tea in the early morning an drew six times his size, and started running to experiment with his new growth. He ended up at a new village, scaring to death the inhabitants with his voice and being, and eating the corpses. He became a Weendigo though his own excess (227).

In the second story, a man asks the parents of rehire daughters hand in marriage. The parents refuse – the man has many wives, and is being greedy, and they don’t want their daughter to be unhappy as a lesser wife. Well, the man takes offence at this, and when he gets home, he performs a ritual (227). The woman, many miles away with her family, becomes very cold and unwell, and ends up eating her own family. When the family doesn’t come back, the rejected suitor volunteers to find them and “claims” the new girl as his, as she has no one to help her and she remembers nothing. After a while, the young woman asks about who she is, and finally, the suitor breaks down and tells her. She only believes it after the oldest wife tells her it’s true. She goes into depression, feels the familiar coldness and aching hunger from before, and throws herself into the fire. In the morning, they find a figurine of a woman in ice, next to a figurine of a baby – she had been pregnant, and she had her revenge (230).

Modern Weendigo’s have taken on the form of people who work in corporations, destroying forests and traditions for cash and personal gain – they are a new greed that destroys communities and cultures, lakes and lands, easily. We need a new champion to defeat them, like Nana’b’oozoo did in his day (237).

Buy the book: The Manitous